The Homespun Beauty of Textile Designer Isabel Farchy’s Patchwork Panels

Much like the patchwork textile panels she creates from vintage fabrics, Isabel Farchy’s journey to her craft is a rich assemblage of influences. Hailing from a creative and curiously-minded family, she first studied politics and later worked as a teacher before pursuing a foundation in furniture design at The Cass. While seemingly disparate focuses, speaking with Isabel, who also founded a charity aimed at improving access to young people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, it becomes clear that she sees creativity as something inherently political. Who gets to live a creative life? And what opportunities exist for making that possible?

These questions became personal when Isabel became a mother four years ago. After having two children, she began to reassess what work meant to her while, at the same time, a renovation left her with large, bare windows. With little time or space to make furniture, she picked up a sewing machine as a way of creating something for her family’s home, meaning she could be there with her children too. “The labour market is designed for men who have partners at home to take care of the children. The nature of caring for small children means it can be hard for new mothers to sustain a traditional career. I had a deep and strong feeling that I just didn’t want to be sitting in front of my desk – I wanted to make stuff. The textiles became a way of combining the necessity to change my working patterns, with this desire to create,” she explains from the kitchen of her De Beauvoir home.

Today, with a number of commissions on the go at any one time, and with ambitions to work at increasingly larger scales, Isabel remains cognisant of how her identity as a mother to two nursery-aged children, and the realities of what that means for her time and ability to work, means for her creative life. “How do I feel about it? I’m not sure entirely, but I’ve been thinking a lot about how women have been traditionally associated with the applied arts because they are crafts you can do from home. Look at the Albers; only much later was Anni recognised for her pivotal contribution as an artist,” she explains.

Here, we’re sharing an edited version of a conversation with Isabel that spanned everything from inherited creativity and the politics of making by hand, to the improvisational joys of dyeing fabric in a family kitchen.

Scura: Let’s start with how you got into textiles – was it something you always knew you wanted to do?

Isabel Farchy: Not at all. I actually came to it through quite a roundabout route. When I had kids, especially my second, I had this really strong instinctive feeling that I just didn’t want to be sitting in front of a desk anymore. I wanted to make things. We’d just done a renovation, and we had these big, bare windows, and I didn’t have time or space to make furniture like I’d studied, so I thought, okay, I’ll get a sewing machine. That’s how it started – making curtains for our home, just as a way of doing something creative that could also fit around the kids.

Scura: You mentioned furniture, what’s your educational background?

Isabel: I studied politics first, then trained as a teacher, and then went on to do a foundation in furniture design at The Cass. It was such a good course, but the wood and metal workshops were quite macho environments. I always felt a bit intimidated asking questions. The technicians were nice, but the vibe was definitely very male. So I started spending more time in the textiles area, partly because it was more welcoming, and partly because I realised I’m not very precise! With textiles, you can make mistakes, unpick things, cut them again. It’s much more forgiving.

Scura: Were there creative influences around you growing up?

Isabel: Yes, definitely. My grandmother was a big influence. She was from Milan and was around that kind of post-war Italian design scene – my dad told me she knew both Gae Aulenti and Luigi Caccia Dominioni well. She made all sorts of things, from handbags to cushions and little pin holders. She basically was an artist, but she was working at home, like so many women then, and I think that’s why she wasn’t really recognised in that way. Looking back, so much of what she made is beautiful. I’ve kept a lot of it and there are pieces all over our house. She’s definitely one of those people who had to make the most of the domestic space as her studio, and that really resonates with me now.

Scura: You work with a lot of vintage and salvaged materials. What draws you to those?

Isabel: I get most of my linen from a wonderful dealer who goes to Hungary and finds these incredible old sheets. They’re so lovely to work with because the textures are beautiful, they’ve got these hand-sewn seams in all the wrong places, but that makes them really interesting. I also use our old family sheets, even baby cot sheets. There’s something about starting with scraps that feels natural to me – I think that comes from my time at The Cass, where I used to scavenge from piles of offcuts. I’ve always worked quite intuitively, more like “George’s Marvellous Medicine” than following a strict plan.

Scura: And British wool has become part of your practice too?

Isabel: Yes. I grew up partly on my aunt’s farm in Sussex and remember seeing all these fleeces just rotting in the barns. British wool has almost no commercial value anymore and actually costs less for farmers to dispose of it than they’d earn selling it. It’s not because it’s bad wool – in fact, there’s one breed called Bluefaced Leicester that’s really fine, almost like merino – but there are fewer people championing it. I’m working with a mill up north that only uses British wool. Wool takes dye so well and you get much richer colours, while also being so soft and warm. I’d really love to use more of it.

Scura: You dye everything yourself, using natural dyes. What’s that process like?

Isabel: Long! You have to pre-treat the fabric by soaking it in soy milk or alum for days, then dye it, then leave it to cure. Sometimes the colours fade, sometimes they deepen. It’s a bit of an alchemy. Indigo is particularly tricky as you need a reducing agent like fructose, and it has to be mixed with iron. I do most of it in the kitchen or outside with an extension lead if it’s smelly. Some dyes I make myself: avocado pits give a pink, pomegranate too. I also get powders from this brilliant woman who trades online – her dyes are great.

Scura: Is that commitment to natural materials and slow processes political for you?

Isabel: I think it is, yeah. I don’t talk about it in a manifesto-y way, but I think making by hand is political. Using what’s already there, working with waste, working slowly; it’s a kind of resistance. And then there’s access. I started a charity called Creative Mentor Network to support young people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds into the creative industries. So much of creativity is about who gets to do it: who has time, space, money, the safety net. That’s always in the back of my mind.

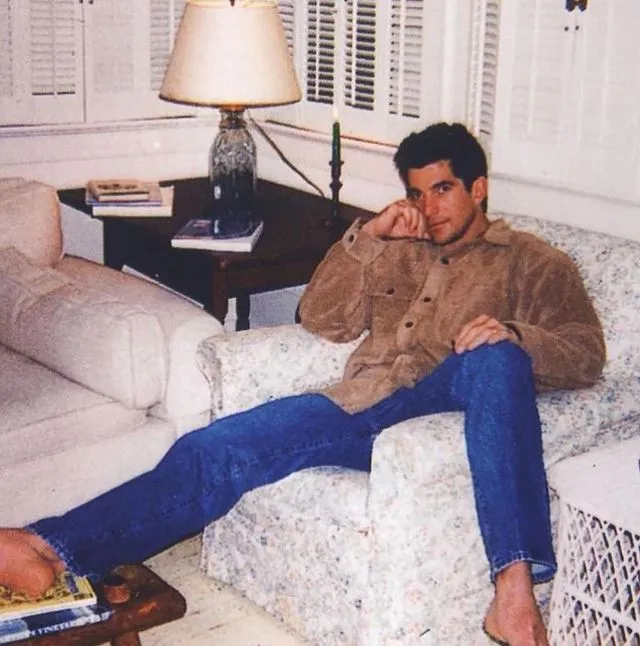

Scura: Your home is very much your studio. How does that shape what you make?

Isabel: It’s huge. I mean, it’s where everything happens. I lay things out in the kitchen, dye on the hob, sew upstairs. In some ways, it’s lovely, being in the space where the work is going to live. I think a lot about light – how the panels soften it, filter it, make a room feel warmer. That sense of cosiness and shelter really appeals to me. I do fantasise about a big studio with enough space to lay everything out properly, but being at home means I’m around for the kids, and that’s something that this different work pattern has allowed me to commit to.

Scura: What role has motherhood played in your creative path?

Isabel: Everything changed after I had kids. I used to be very corporate in my approach to work and organised my life so that work and home were very separate. I led the charity and was always on the go. After two children, that was no longer possible and I needed to be at home more. Because of that, our home environment became more important. I had a long-held ambition for making and creating to become my job, and somehow, with the birth of my kids, that became harder to ignore.

The pressure to reorganise a career is something I think a lot of women feel, but it’s not always talked about. Working flexibly and from home more can be incredibly frustrating because you’re tired, you’re interrupted all the time. But, for me, it also offers a different kind of creativity. I have to be more fluid, more responsive. I’ve been thinking a lot about how women have historically worked in applied arts. It’s become more obvious why: as a woman who was creative, you had to find ways of making that were possible in the home, with a child on your hip.

Scura: What does a typical work day look like?

Isabel: If the kids are at nursery, I’ll start by laying out fabrics downstairs. I hang things up, pin pieces, look at how the colours interact. Then I’ll move upstairs to sew. The dyeing process happens in the kitchen, often with things bubbling away while I’m doing other stuff. It’s not especially glamorous, but it works for now. I’ve tried to find a studio space before, but by the time I’d get there and back, I’d lose half the day.

Scura: And what are you hoping for next?

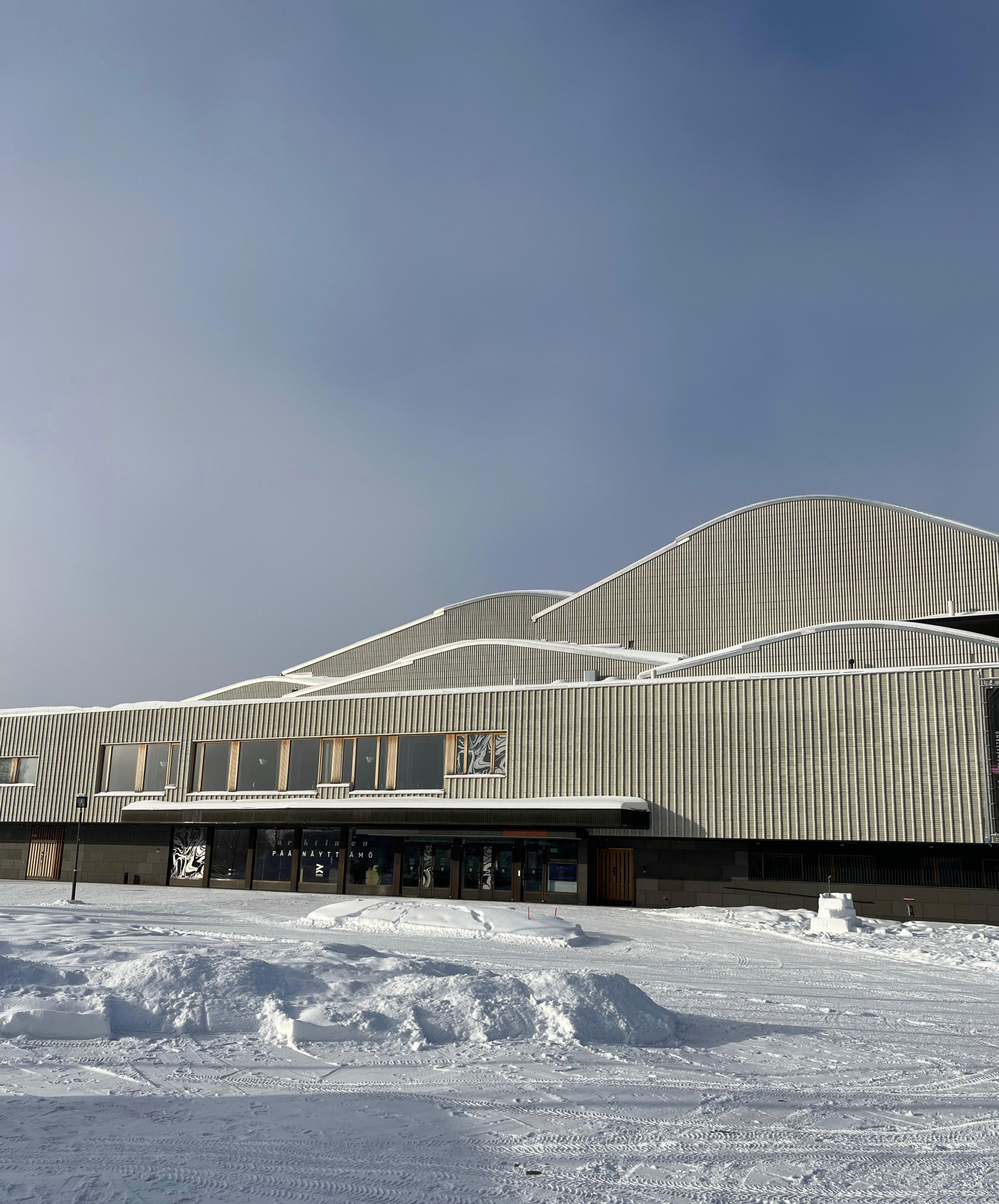

Isabel: I’d love to work on a bigger scale. There’s a potential project in Copenhagen I’m excited about. Doing something for a public or commercial space would be really fun. I’ve got loads of ideas outside of textiles too for sculptural things, maybe even using driftwood or found objects. We’re going to Italy for a few months to stay with my dad, and I’m hoping to do some dyeing there and maybe make something from the landscape. One day I’d love a proper studio, but this is working fine for now.