Luke Malaney’s Work is Always in Motion

When I speak to woodworker Luke Malaney for this piece, he joins our call not long after getting back from a skate trip in Buffalo, New York, where he has been on his board shooting for Traffic, a Philadelphia-based skatewear brand. Now back in Brooklyn, in his Red Hook apartment, he is keep to get back to his workshop. But before doing so, he must endure my attempts to coax out a connection between skating (which he has been doing for 20 years) and his woodworking practice. It is tangential, maybe, but worth a shot…

To my surprise, Luke lights up at this suggestion. “Three four years ago, I wouldn’t have seen how the two things correlate, but as I’ve been diving deeper into my own work I definitely see a correlation,” he says. And just what is that? “Skating trains you to read the built environment differently: to see architecture not as static but as something to move through, reinterpret, and reimagine,” Luke explains. “I approach my work in the shop not with a predetermined conclusion but as an exploration, allowing form and material to shift direction, much like discovering a new street spot, or a different way to skate a familiar one. In both practices, perception and possibility are inseparable.”

He traces his interest in woodworking back to school. “I took a double period of shop and just liked making objects that I knew would last,” he says. “It kind of made my brain burp, as I like to say. I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since.” Alongside the making came a steady habit of note-taking. “Growing up I always had a little book, which I’d fill with drawings and writing.”

Formal training followed. After high school he weighed up a year off to skate, but his mum nudged him towards college. “She pushed me to go,” he says. He enrolled at a SUNY state school in the Catskills to study occupational studies. “The first year was general carpentry, a trade college vibe, then you branch out into remodelling, masonry or woodworking. I went into woodworking and made a couple of smaller pieces.” The curriculum gave him a survey of type and history. “We learned Shaker and Victorian styles, and I got inspired by Japanese architecture and designers – Nakashima and those kinds of names.”

After graduation came the 2008 financial crash, so he moved home on Long Island and walked into a small workshop for an interview. “I had this feeling, this is where I need to be,” he remembers. “Everything was solid wood, from doors to furniture. The guy’s name was Ramo; he came from Rome and started his own shop. I learned pretty much everything I know from him. He was kind of a lunatic.” The lessons were strict in the best way: slow down, look closely, start again if it isn’t right.

After that, he joined a design–build fabrication shop inside an old building known as the Candy Factory in Fort Greene. “Small crew, inspiring building full of painters, sculptors, jewellery, all under one roof,” he says. Much of the day job was high-end millwork and cabinetry, but the space became an after-hours laboratory. “I had a set of keys. That’s when I started really exploring, making things for myself, then for friends, then commissions.”

That mix of structure and self-direction still defines how he works. “You learn the rules well enough to make a legit piece, then you can play,” he says. “You’ve got the experience to fall back on when you bend or break them.” His process stays loose by design. “I work pretty spontaneously. I’ll get myself into a place where I’m like, ‘Oh no, how am I going to get out of this?’ Then I tone it down or ground it. I fall back on the traditional skills to keep going.”

The evolution of his style has been cyclical rather than linear. “I went pretty sculptural for a minute,” he says. “Now I’m touching back on older work, which is defined by straighter, more architectural lines, and blending something whimsical with a more traditional piece of furniture. I’m trying to refine that mix and see where it goes.” Most works start with quick paper sketches. “Very rough and loose, just to visualise the piece,” he says. “I’m resourceful with material. I look at what I have, which might be offcuts or reclaimed wood, and keep the process open. I don’t want to be stuck to a drawing in CAD. I’d rather discover details in the making.”

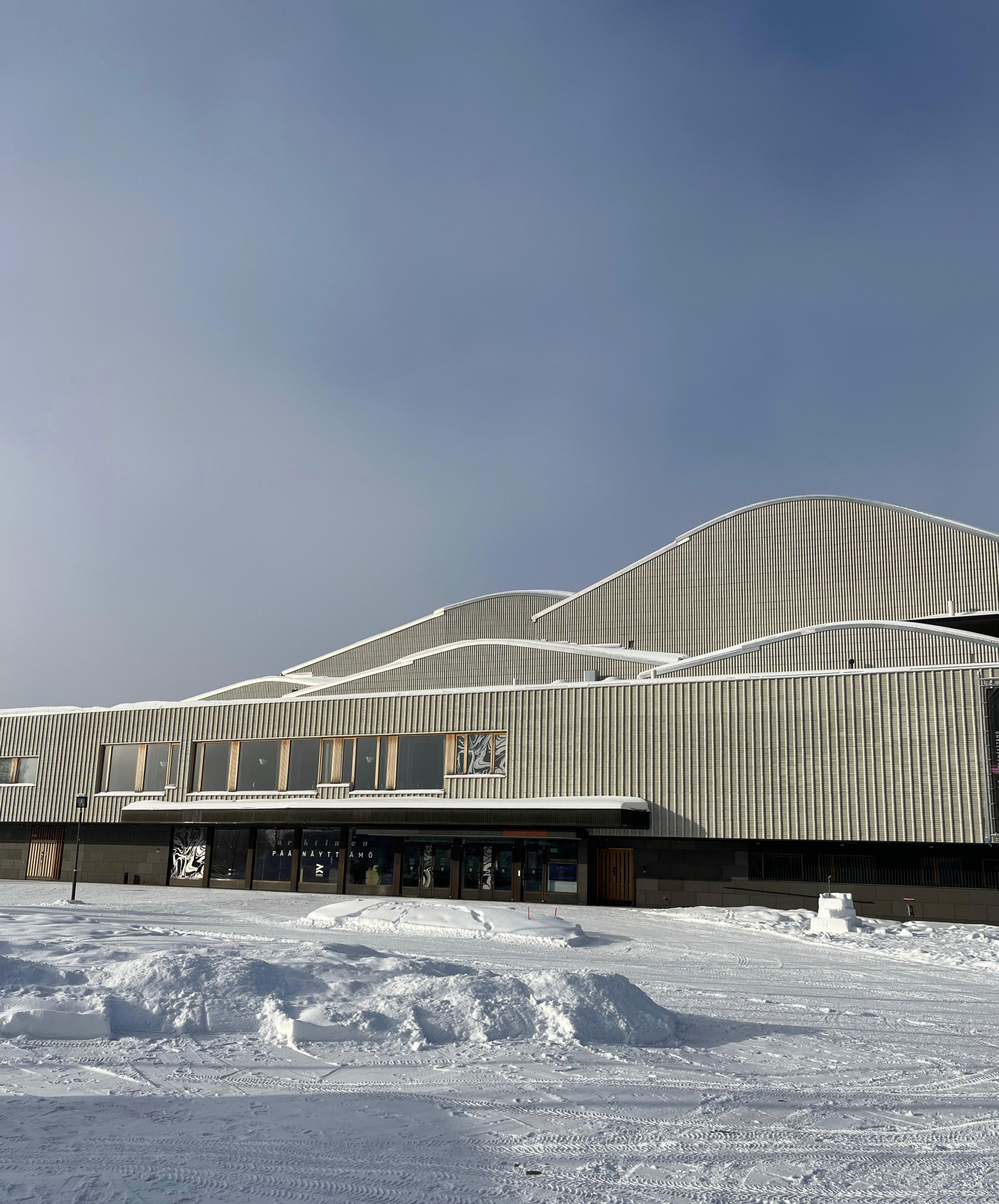

That openness is visible in current work showing in Paris for Objective Gallery’s “Who Has the Time?” at THEMA Art + Design Fair (22–26 October 2025). Luke’s contribution is a tall “skinny-boy” cabinet. “It’s an open cabinet, almost seven feet, with a big drawer that breaks up the middle,” he says. A profile borrowed from vernacular buildings informs its shape. “I’m put a triangular, roof-like structure on top. I love looking at barns and wood sheds when I’m upstate or in Vermont.”

Then there is the wood itself. “I stumbled on a local mill guy in Pennsylvania by total chance,” he says. “We were staying on a small farm; the owner was a woodworker and introduced me to his guy who works with local arborists and fallen trees. It’s all air-dried.” On a return visit he found a cache of pine boards. “They’d been air-drying for years in his barn. The resin had marbled through every board. It was dry enough to work, not sticky like green pine, and I couldn’t not take it.” Those boards dictated the exterior of the piece now in Paris. “I lightly hand-sanded and did a black wash to show the marbling, really to let the resin read.”

Copper is another thread running through his work, sometimes as a quiet structural element, sometimes as the headline. “I’ve worked with copper for a long time,” he says. “Early on I made a little side table with 20 or so copper plumbing pipes protruding from the bottom. I called it the Jellyfish Table. I also did a nightstand with a copper drawer.” A few years ago he decided to scale up. “I wanted to work with the same 16-ounce sheets roofers use for flashing and gutters. I found a supplier and started experimenting with shades.”

The Kansas Lamp came out of that phase. “In my head it started as a classic floor-lamp shade,” he says. “The sheet wasn’t cooperating, so I hammered and hand-bent it. I kept the edges sharp at first, then added a clay-epoxy border to soften the cut edges.” He began hand-folding the perimeter into a simple quarter-inch fold hammered down to a smooth line, and testing surface treatments. “I’ve been playing with patinas and torching. There’s a richness to the colour, and because copper is soft you can manipulate it.” The wooden base and shelf bring the tone back to earth. “I’m always thinking about how colour sits with, say, cherry or another timber, how the whole thing reads.”

Home has become another site for trials that come with the advantage of being practical and relatively low-stakes. Last spring Luke and his partner, Maria, moved into a circa-1900 place in Red Hook: slanted yellow-and-white pine floors, a brick fireplace, and windows that needed work. The charm outweighed the flaws and the price made it feasible. He’s been furnishing it slowly with pieces he designs and builds, sometimes levelling around the building’s eccentricities – quite literally, as in the bedroom, where the platform bed he made was adjusted to accommodate the wonky flooring.

A recent radiator cover shows how he folds rule-breaking into function. “Radiator covers solve a problem, but they can add a bit of flair,” he says. He built theirs tall enough to act as extra counter space, with a shallow drawer, and designed it to be removable because they’re renting. The finish experiments with a technique he’s been refining. “Those little spotted marks, that’s wood glue,” he says. “You’re taught to always clean up glue, never show it. But I started ‘painting’ with it by letting it dry, lightly sand, then wash over it. It pops when it’s finished. It’s like putting the thing that actually holds furniture together on a pedestal instead of hiding it.” The approach has travelled into commissioned work too: a recent nightstand carries the same glue-as-paint surface.

It’s this freedom to create, to experiment, to work things out by doing that Luke sees as most parallel to the other obsession in his life, skating. “By default, skaters see their surroundings differently,” he says. “You might skate a famous spot, but I’m more interested in finding a different way to use it, or finding something overlooked.” The same logic guides the making of a bench. “I’ll add a detail where you wouldn’t expect it – a curve here, a pop of colour there – and then step back and see if it holds.” What ties it together is autonomy as a driving force of creativity, that all important spirit of independence. “It’s up to me what I put out and how I make it,” he says. “You fall, you fail, you keep going. Learn the rules, then forget them when you need to. Create your own way.”